Isaac Hayes Wallpaper Generator - Volumetric light scattering, 1 of 2

This post is greatly based on the Nvidia GPU Gem on volumetric light scattering. Here I walk you through the formulae and core concepts. I highly recommend reading that one instead, and come back only if you couldn’t follow, or for fun.

If you’re unfamiliar with computer graphics, I highly recommend you to watch John Carmack’s talk on lighting and rendering.

Often there’s one rendering effect that has me in awe everytime I see it. The first one I remember was normal mapping. While playing videogames I used to walk towards a wall that had a light bulb nearby, and then I spent a good 10 minutes just moving near the wall, seeing how the light behaved.

Lately I found myself doing the same thing while playing The Witcher 3, I just forwarded time until the sun was low enough so I could just toy with the light shaft effects between the trees. And then again, I spend a shameful amount of time just walking back and forth seeing how these patterns would unfold.

For the sake of me actually playing videogames instead of just being mesmerized by technical feats, I decided to understand how light shafts are generated and what’s the theory behind it.

My hope here is to give any reader a shallow but thorough overview of computer graphics rendering and physically based rendering effects. These two concepts are rather tangent, in the sense that computer graphics will not use the actual physical formulae, but hacky approximations.

Rendering equation review

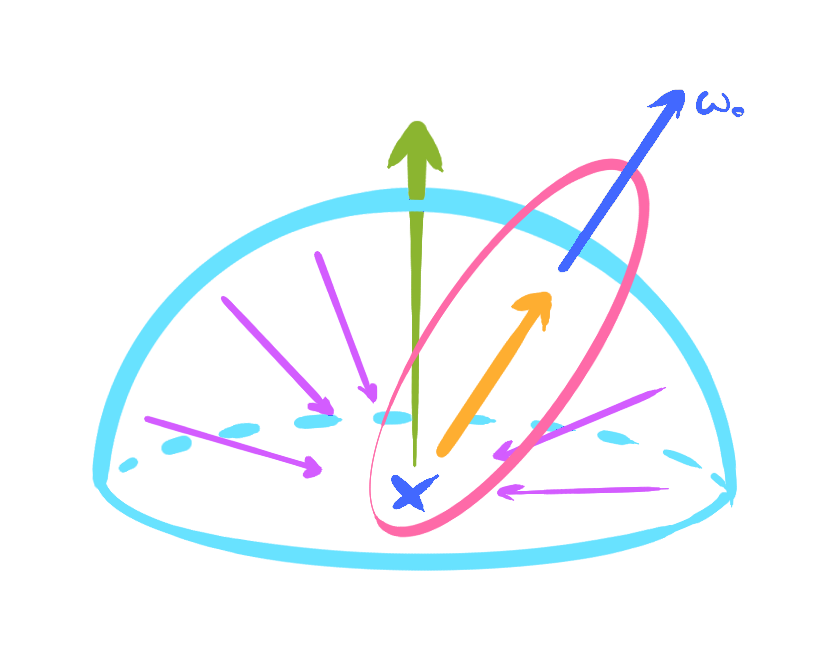

This drawing and explanation were featured in CHI’22: ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

To find the light towards the viewer from a specific point, we sum the light emitted from such point plus the integral within the unit hemisphere of the light coming from a any given direction multiplied by the chances of such light rays bouncing towards the viewer1 and also by the irradiance factor over the normal at the point.2\(^,\)3

Note that incoming light is also computed by that very formula, which makes this exhaustingly recursive.

So, think about the pixel you’re reading right now, your screen is probably emitting more light than it transmits from other sources, if you have a glossy screen, then you see your own reflection. Meaning that for every point in your screen, light is reflected along the surface normal (perpendicular to your screen) in a specular fashion.

If you have a non-glossy screen, then the light bouncing from other light sources is more evenly distributed over the reflection hemisphere, hence not forming a clear image as a result, but a diffuse image instead.

Volumetric light scattering equations

Light, as the electromagnetic radiation it is, interacts with matter mainly in two ways4:

- Absorption (The photons disappear)

- Scattering (The photons change their direction)

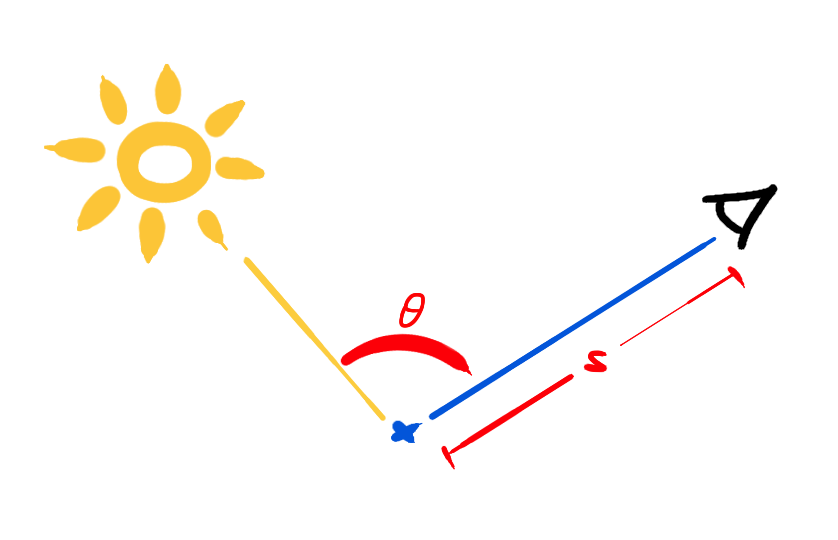

In both cases the transmitted intensity \(I\) decreases exponentially. Being \(\tau\) the extinction coefficient composed of light absortion and out-scattering, and \(s\) the thickness of the medium we traverse, we use an exponential function over \(e\) to represent the extinction coefficient5:

\[I=I_\text{o} · e^{-\tau s}\]This helps us understand how scattering is first modelled in Nvidia’s GPU gem on volumetric light scattering6. Let \(s\) be the distance through the media and \(\theta\) the angle between the viewer and the light beam:

The light accounting for volumetric scattering is a linear interpolation weighed by the extinction constant. Note how we interpolate between the light computed at a given point and the light due to scattering, which is a product of the source illumination from the sun (or light source) and the angular scattering term according to Rayleigh and Mie properties.

Let’s talk a bit about the Rayleigh and Mie term, it’s a function of particle size, shape and composition of the medium we traverse. This component and the extinction coefficient model the atmosphere or space through which light scatters.

In a nutshell, smaller particles scatter according to the Rayleigh model, and larger particles according to Mie. In this context we consider smaller particles the ones much smaller than the wavelength of incoming light.

This means Rayleigh scattering bounces off smaller wavelengths, such as the blue spectrum. Mie on the other hand, is not dependent on wavelength, and it scatters the whole spectrum of light. Clouds are white because sunlight is white.

![Rayleigh and Mie scattering describes how light scatters off of molecules in a medium depending on the size of those molecules. Smaller molecules respond to Mie scattering more than Rayleigh and viceversa.[^44]](/images/rayleigh-meow.png)

Occlusion

Last but not least, we need to take occluders into the equation. Let \(\phi\) represent the ray from the light emitter towards the observed point:

\[L(s,\,\theta,\,\phi) = (1 \,-\, \textcolor{orange}{D(\phi)}{)} \textcolor{red}{\,L(s,\,\theta)}\]Is the light accounting for both volumetric light scattering and the opacity term of all occluders, which is the total opacity of the occluders along the ray.

This term accumulates objects’ opacity. If there’s a solid object between light source and observer all light energy will be zeroed, however we must account for indirect light as well as seen in eq. 1.

Wrap up

This covers a shallow walk through the theory of visible light and atmospheric scattering. With the information above we should be able to compute the light energy towards the viewer for any point in space, note that we left out things like light wavelength for simplicity. I hope you have enough to get started.

In the next entry I will demonstrate these concepts implementing volumetric shafts of light with GLSL, completely dismissing all we learnt here and just hacking our way to rendered images.